Charles Cohen: Synthesis and Context

by Jordan Rothlein

Some of the most vital electronic music of late was recorded around 30 years ago by a little-known US artist named Charles Cohen. Resident Advisor's Jordan Rothlein traveled to his home in Philadelphia to hear his story.

→ This article was originally published on Resident Advisor.

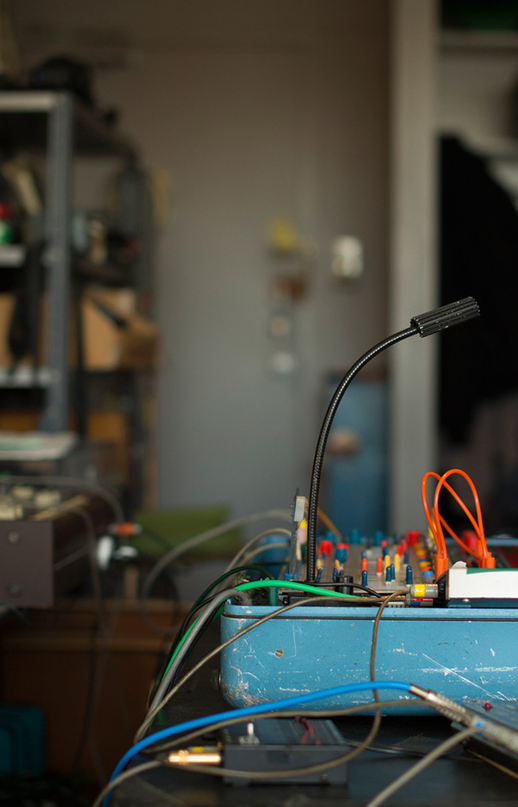

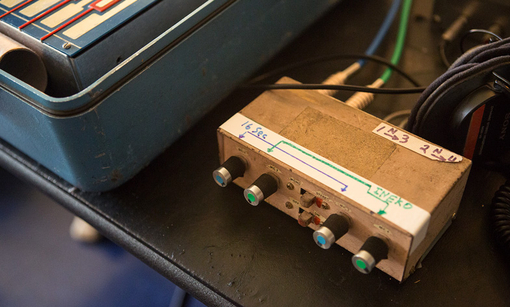

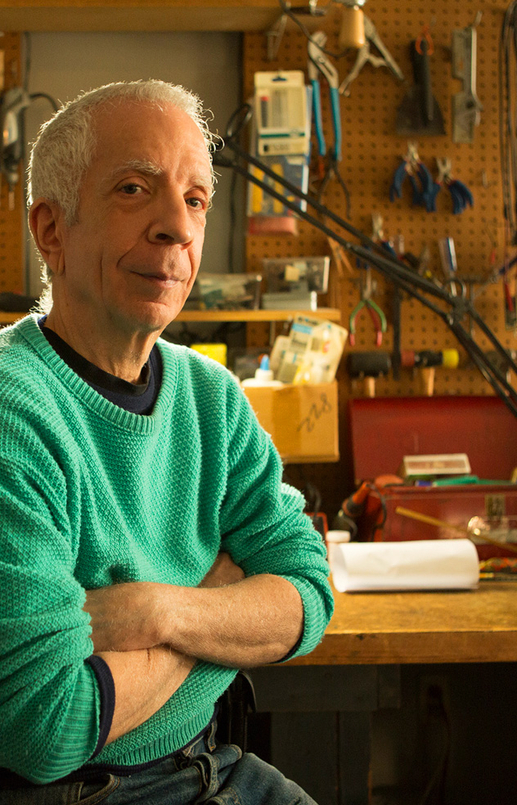

Charles Cohen's musical life fits in a baby blue suitcase. When I visited him at his Philadelphia apartment on an impossibly frigid afternoon recently, it sat open on a folding table in the middle of his living room. You'd imagine it's in that position often. The room seems to orbit it, with analog recording ephemera sat on desks and shelves along one wall and a workshop, ostensibly for servicing the suitcase's contents, lining the other. The usual creature comforts of a small city apartment—a dining set, a low couch—sit on the outskirts of the space and feel like token inclusions.

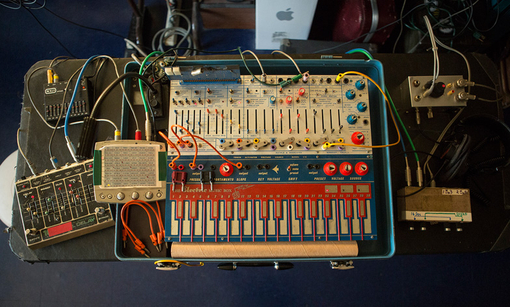

While Cohen stepped into the kitchen to brew tea, I stood by the suitcase and peered in. I was looking at a Buchla Music Easel, an obscurity by pioneering synthesizer designer Donald Buchla. Synthesists like Morton Subotnick, a close Buchla associate, favored Buchla systems for representing a paradigm shift from pre-synthesizer instruments; if a Minimoog can make sounds that have never existed before in the history of music, the argument goes, why should we have to play them like a piano? Buchla synths like the one Subotnick used to record Silver Apples Of The Moon, however, took up a lot of space, and getting them to make sound didn't translate to much of a stage show.

The Music Easel, which was rumored to have been manufactured in hilariously small quantities in the 1970s (they've since gone back into production), brought their sound and some of Buchla's typically irreverent workflow to a more portable package. Rather than be hidden behind a wall of modules, a player could sit the single-oscillator Music Easel flat in front of him. It also boasted a kind of metallic keyboard for triggering sounds.

Cohen's relationship with the Music Easel he bought in the late '70s didn't begin well—it broke within two months, and he had to send it back to Buchla to swap out some chips. It was uphill from there. "I knew there was something special," he says. "I didn't quite understand how you used it. I couldn't really feel like I was controlling it, so I gradually started playing some other instruments. Over the years I kept on coming back to it, and eventually it came to the point where I had this realization that actually I could do everything I needed to do with just this."

Returning with tea, Cohen asks me if I play. I tell him that I do—a little—and he beckons into the suitcase. Buchla systems aren't always easy to get going—"Once I figured out, 'Oh, Don's brain works in mirrors!' it all started to make sense," says "Buchla guru" Todd Barton to not especially comforting effect in a video lecture on the Music Easel—but the keyboard here presented an obvious place to start. I let a finger graze a key, and at the moment it touched I heard the sort of rich, texturally complex voice that's all over Cohen's archival recordings, some of which appeared for the first time across a string of releases late last year on Morphine Records. The sound itself was indelible, but even in my timid playing I could sense the instrument's potential for expressiveness, the x-factor that makes even Cohen's most abstract work so emotional and invigorating.

You sense it's the Music Easel's musicality that makes it so valuable to him, because for Cohen, sound is nothing if not participatory. He'd been inspired by the tones he heard in Subotnick's music, but it was Sun Ra and the free jazz pianist Cecil Taylor who shaped Cohen's perception of electronic music as a freely flowing live performance. His experiences as an era-spanning member of Philadelphia's avant-garde music scene, where he's found kindred spirits from jazz to the scruffier side of electronic music, helped root his music in community and collaboration. When I ask him if he listens to many new records, he categorically says no. "Usually if I'm in a music mood, I'd rather just play," he says. "I rarely feel like I have the time to sit down, put on some music and sit and listen to somebody's piece all the way through. I'd rather just be playing."

Cohen began his career making scores for theater and dance productions and working as a sound designer at Temple University. His interests moved into improvisation the longer he played, drawing him away from more traditional composition and studio work and further into free jazz, cosmic music and noise. "Dancers rehearse so darn much," he says of those days. "By the time it got to the performance, I was bored of all that. Now my idea about performance is I show up, I play, I try and enjoy myself and then I forget it." With just one main oscillator, the Music Easel can only produce one sound at a time, but it's capable of everything from searing leads to ambient textures to biting rhythmic tones, so he'd work with an eight-track recorder to create multilayer compositions.

The music on Cohen's Morphine releases—The Middle Distance, Group Motion and Music For Dance And Theater, plus a 12-inch featuring the track "Dance Of The Spiritcatchers" remixed by label boss Morphosis—comes from this era. As Cohen tells it, a friend of his was at a rave in Berlin and recognized one of the tracks as something Cohen had made 20 or 30 years ago. The friend struck up a conversation with the DJ afterward and realized the DJ didn't know anything about the artist behind the record. Somehow word of this got around to Morphosis, AKA Rabih Beaini, who had released music from Cohen's fellow Philadelphian electronic improvisers Metasplice. Beaini wrote to Cohen asking if he had any more music like the mystery record from the rave.

As it happened, he had a closet full of the stuff, most of it never intended for release beyond the dance production or theater piece they were recorded for. "Once that was over that was it," he says. "They just went into the archive." He started pulling out the old tapes, digitizing them and sending them to Beaini in Berlin. He wanted more and more of the material, and Cohen eventually sent him just about everything that was in decent enough shape to be extracted from the tapes. (He says there's still plenty of recordings in there, but the tapes are too deteriorated at this point to produce viable music.) Other than gathering the music and doing a bit of mastering and restoration to the digitized recordings, he gave Beaini free reign to sequence and release the material. "He's the first person who came along and said, 'You know, let's do something really major,' and I said, 'Why not.' His enthusiasm is infectious."

The releases put Cohen in the somewhat awkward position of achieving international recognition for music he made decades ago, in a compositional style he no longer practices. "I did that for many years, and it was a lot of fun," Cohen says of integrating tape into his music, "but eventually I slowly got into just playing live. I've tried doing some recordings, but the only thing that works is just jamming." (Some of these jams end up as "Beeps Of The Week" on Cohen's SoundCloud page.) His approach to music these days is most closely linked to Pauline Oliveros, whose "deep listening," emphasizing a sensitivity to the unconscious over technique, Cohen has studied and clearly taken to heart. Beaini is keen for him to put out some new material, but Cohen isn't sure it'll work. "It's a funny business, you know, just being in the right mood and having everything kind of work," he says. "It's unpredictable. Rabih keeps saying he wants new material. I keep scratching my head thinking, 'How am I gonna do that?'"

For the moment, Cohen's focus is on a string of live dates in Europe around Berlin's CTM Festival this month. He's played in Europe before with other ensembles, but these shows will be his first time playing solo on the continent. He's opted to travel there with a stripped-back setup, which is how he had the blue suitcase configured on the day I visited—aside from a few worn effects boxes, it will just be Cohen and the Music Easel on stage. In contrast to the lushness of some of the Morphine material, these performances will be "bare bones, stripped down, just a single sound trying to express the timbres of the instrument." He'd considered traveling with more gear—"loopers and whatnot"—but when he began plotting out "this mythical airport journey, this mile-long hallway," he thought better of burdening himself with so much luggage. Beaini assured him he shouldn't be self-conscious about presenting such a raw performance. "Charles, you know, people just want to hear you and the Buchla, that's all you need," Cohen recalls him saying. CTM will be the first time the two have met face to face.

When Cohen plays his Music Easel these days, he turns it on and starts from wherever he left off last time, manipulating the sound and then leaving it for another session. I wonder how much rehearsal that sort of performance requires—especially considering the years Cohen has spent making the instrument a kind of direct extension of his creative impulse—and he confirms that the next few weeks are more about preparing for the particulars of his trip abroad than working on music for the performances. He's keeping this as loose as ever, even if the passing of the years has become difficult to ignore. Now in his late 60s, Cohen was recently diagnosed with Parkinson's, and while his symptoms have thus far caused "more annoyance and occasional embarrassment than interfering with music-making," they've spurred him to place new importance on his musical life. "It's time to prioritize," he tells me in an email exchange after our meeting, but I wonder if Cohen, the consummate improviser, is better prepared to deal with uncertainty than others would be.

Though he could have conceivably found a new, wider audience years back, he doesn't bemoan his approach finding favor now, when time may be tighter for him but his music has never sounded fresher. "Maybe I'd better not think about that too much," he says. "I really just need to do what's fun and what I enjoy. I'll start thinking about my place in history, and you know everything will go to hell, so I'd better not."